|

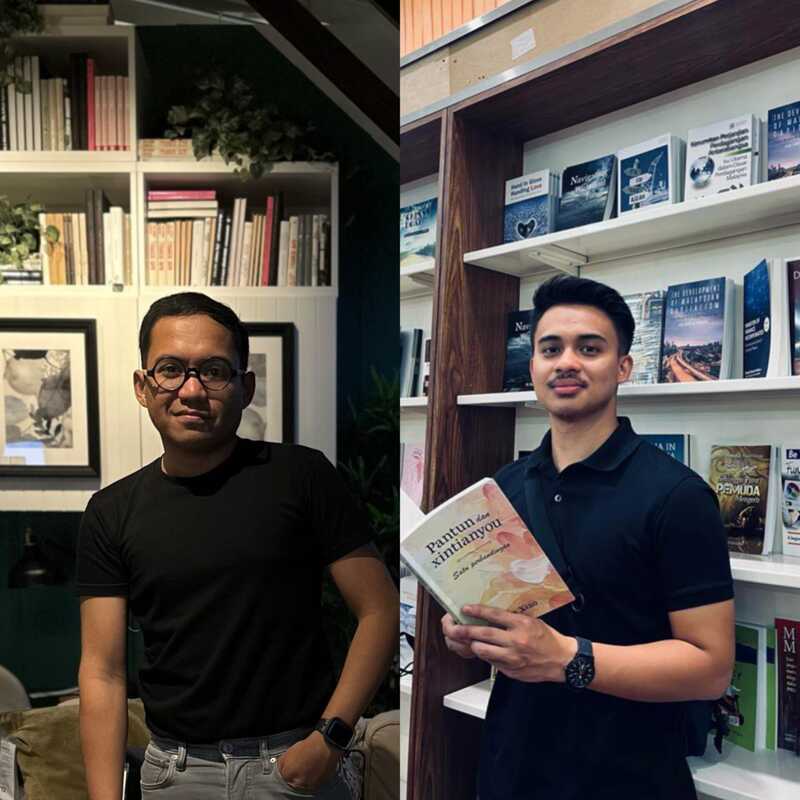

by Abdul Aziz bin Arsyad & Mohammad Shalihin Azim bin Ismail Teaching practicum is a crucial component of teacher training. It is in fact a rite of passage for every teacher. For most student teachers, it marks their first experience being on the other side of the classroom, with a pair of scrutinizing eyes following their every move. It is therefore understandably a jitter-inducing experience, even for the calmest. We decided to take on this writing on a very simple premise – that very rarely we have seen teacher educators (henceforth, supervisors) and student teachers (henceforth, supervisees) share what they hope for from each other going into practicum beyond what is stipulated on the observation forms. After all, teaching is more than having a checklist and ticking the items off that list. While these items have their own merits, there are other expectations which are sometimes left unaddressed by both supervisors and supervisees that can lead to frustration and dissatisfaction. To come up with these shared expectations, we first decided to each go independently blind with our respective lists. Next, we exchanged our lists and identified common threads. Having done so, here are the five (5) things supervisors and supervisees expect from each other during teaching practicum. 1. Engagement in Reflection & DialogueThe first is engagement in reflection and dialogue. From the perspective of supervisees, having supervisors who will dedicate adequate time to engage in reflection and dialogue or what the student teachers in Mauri et al. (2019) describe as ‘a climate of genuinely shared conversation’ is of utmost importance. While this may be a common practice among supervisors particularly in the form of constructive feedback after every supervision, there have been woeful instances when supervisors leave the classroom before the lesson ends, making them unable to provide specific feedback about the lesson conducted. Instead, the reflection is rather general and at times superficial. As for supervisors, engagement in reflection and dialogue comes in the form of supervisee’s willingness to reach out for extended discussion and support. While the space for reflection and dialogue after each observation is typically afforded to supervisees, they are also encouraged to reach out should they need further discussion to reflect on a particular lesson or critical incident. Teaching practicum can be quite a challenging period for both supervisees and supervisors. For supervisees, this transition could be instantly overwhelming, leaving them feeling like a ‘chameleon’ or ‘lonely shepherd’ (Zhu & Zhu, 2018), as they try to navigate through the unfamiliar territory to meet the demand of various stakeholders including their own teaching institution, the school they are attached to as well as the students they are in charge of. For supervisors, supervising a group of students (who are oftentimes geographically scattered) comes on top of their usual routine of teaching and assessing. Thus, the initiative from supervisees to reach out for support is not only welcome, but also encouraged. 2. Sound (Pedagogical) Content KnowledgeThe second common thread pertains to content knowledge. Any aspiring novice wishes to be under the tutelage of an expert in a particular subject matter. When it comes to practicum supervisors, this subject matter is stretched further to include not just the content side of it, but also its practical implementation in classroom and how this knowledge is effectively taught, known as pedagogical content knowledge. For instance, lesson planning is considered an indispensable part of teaching and it requires integrated understanding of many interdependent aspects including learning objectives, content selection and instructional approaches. Therefore, supervisees rely on supervisors (other than the mentor teachers assigned) and their sound pedagogical content knowledge to guide them to create a well-thought-out lesson plan that does not only look good on paper but is also realistically executable. Thus, supervisees expect their supervisors to have this knowledge to help them develop their own autonomy, rather than just someone who prescribes, supervises and evaluates (Portman & Ruwaida, 2019). While supervisors will not expect their supervisees to have this nuanced mastery of pedagogical content knowledge at this point of their teaching odyssey, they do expect sound content knowledge so that their supervisees can command the confidence of the students. Over the years, what has been observed is that sometimes supervisees are unable to even master basic concepts in their respective subjects, which they should have in the years leading up to the practicum period, as how teacher training is typically structured. Such inadequacy can compromise their credibility in the eyes of the students. Having sound mastery of content knowledge is prerequisite to bridge theory and practice, which is expected to take place during teaching practicum (Sulistiyo et al., 2017). 3. Situated Understanding of StudentsThe meaning of the word ‘student’ in this context is two-fold. For supervisees, they consider themselves as students who expect their supervisors to have situated understanding – defined in this writing as contextualised knowledge of individuals – of who they are and their own strengths and weaknesses. Some supervisees may not realise a particular advantage that they have until it is pointed out by their supervisors. This can range from their inherent ability to manage student behaviour effectively, engage students in learning through the use of multimodal learning materials, motivating students through affectively appealing encouragement or even helping students understand their lessons through their own various talents like singing, playing musical instrument or drawing. Making them realise their strengths and potential will help supervisees feel seen, understood, and acknowledged, which is crucial to build up their self-esteem at this stage. As for supervisors, they expect the supervisees to have situated understanding of their students in the classroom. While a mere couple of months may feel too short to achieve this capacity, it is still within possibility since they are usually handling manageable number of classes based on the required teaching periods, as per general guideline of teaching practicum. This situated understanding comes in the form of general grasp of students’ proficiency and learning ability as well as cultural profile including their students’ linguistic, social and economic backgrounds, which in a broader sense requires intercultural understanding (Steele & Leming, 2022). It is unfortunate to see that sometimes supervisees cannot even recall their students’ names, which is the first, fundamental step to nurture healthy student-teacher relationships. Some supervisees who have shown commendable situated understanding of their students use this to their advantage to excel during teaching practicum as their students are more participative, engaged and bonding. 4. Innovative Instinct and InclinationInterestingly, what supervisees also expect from their supervisors is someone with innovative instinct and inclination. This can come in many different forms including suggestions for useful and fun tools to be integrated into their lessons as well as theoretical and practical guidance to help them engage in classroom research and innovation, which most supervisors have first-hand experience in. While some supervisees acknowledge the importance of classroom research and innovation, they feel inadequate to engage. It is therefore understandable why they would expect their supervisors to have innovative instinct and inclination to help them take the first step into this professional development, even during teaching practicum (Mukeredzi, 2015). This is also a two-way street. For supervisors, teaching practicum is also an opportunity for them to learn from the supervisees about new ideas and technological tools that these young supervisees have in their repertoire and arsenal. While they may have amassed wealth of teaching knowledge, experience and best practices over the years ready to be disseminated with their supervisees, some (not all, sadly) supervisors are ready to be pleasantly surprised by their students’ creativity and innovative instinct in the delivery of their lessons. In fact, they are even ready to push these supervisees to document their teaching innovations for competition and intellectual property purposes. Above all, what this ultimately indicates is their predisposition to solve problems and teach better, one of the hallmarks of a thinking teacher who is continuously reflecting and adjusting (Christiansen, Österling & Skog, 2021). 5. Transparency, Accountability and AgencyLastly the elephant in the room – the issue of transparency and accountability. It goes without saying that all supervisees hope to at least achieve a pass in their teaching practicum as a prerequisite to graduate. Regrettably for some, this desire means putting up with supervisors who do not show transparency and accountability in carrying out their duties. This includes not meeting the required number of practicum observations, unwilling to properly guide their supervisees as well as showing lack of concentration and interest while observing in the classroom due to various reasons. For these supervisees, it leaves them feeling dejected and discouraged, particularly when they have done their best to excel in or have expected to be well-guided during their teaching practicum. This expectation too is mutual. There are also instances in which supervisors have to deal with supervisees who have unremorsefully displayed compromised transparency and accountability in conducting their teaching practicum. This includes repeated tardiness or frequent absences from schools for dubious reasons, missing fundamental documentations like lesson plans or teaching materials and the sheer refusal to cooperate with mentor teachers or get involved in other aspects of the practicum experience. Lamentably, some supervisors are instructed not to fail their problematic supervisees in the name of pity, second chances and ‘keeping the record clean and intact’. Although these cases involving supervisors and supervisees are few and far between, they must be addressed accordingly. Supervisors and supervisees deserve to expect (and be expected from) not just transparency and accountability, but also agency, understood as the capacity to take action (Dargusch & Charteris, 2018) in the absence of both. ConclusionWe would like to end this writing by borrowing the words of Portman and Ruwaida in their work that is aptly titled Student Teaching Practicum: Are We Doing it the Right Way? written in 2019, in which they profoundly posit that “In modern societies, the roles of teacher educators and student teachers have changed as learning and teaching have become a lifelong process of trial, error, and inquiry rather than an end to itself”. Is there a space that embodies this triad of trial, error and inquiry more perfectly for both supervisors and supervisees than teaching practicum does? And as how the triad has a meeting point, that’s how we hope that the sharing of these common expectations will help both supervisors and supervisees meet each other halfway. Published on: 14 July 2023 ReferencesChristiansen, I. M., Österling, L., & Skog, K. (2021). Images of the desired teacher in practicum observation protocols. Research Papers in Education, 36(4), 439–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1678064 Dargusch, J. & Charteris, J. (2018). 'Nobody is watching but everything I do is measured': Teacher accountability, learner agency and the crisis of control. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(10), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43.n10.2 Mauri, T., Onrubia, J., Colomina, R., & Clarà, M. (2019). Sharing initial teacher education between school and university: participants’ perceptions of their roles and learning. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 25(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1601076 Mukeredzi, T. G. (2015). Creating space for pre-service teacher professional development during practicum: A teacher educator’s self-study. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n2.9 Portman, D. & Ruwaida, A. R. (2019). Student teaching practicum: are we doing it the right way? Journal of Education for Teaching : JET, 45(5), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1674566 Steele, A. R. & Leming, T. (2022). Exploring student teachers’ development of intercultural understanding in teacher education practice. Journal of Peace Education, 19(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2022.2030688 Sulistiyo, U., Mukminin, A., Abdurrahman, K., & Haryanto, E. (2017). Learning to teach: A case study of student teachers’ practicum and policy recommendations. Qualitative Report, 22(3), 712–. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2671 Zhu, J. & Zhu, G. (2018). Understanding student teachers’ professional identity transformation through metaphor: an international perspective. Journal of Education for Teaching : JET, 44(4), 500–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1450819 AuthorsAbdul Aziz bin Arsyad has served in the field of ELT and education for more than a decade. He graduated from Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) as a KPM Scholar with First Class Honours in B. Ed TESL in 2011. In 2019, he became the recipient of Chevening Scholarship, a prestigious British Government scholarship to further his studies in MSc in TESOL at Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He graduated with Distinction in 2020. Upon returning to Malaysia, he served as a teacher educator at the Institute of Teacher Education, Tawau Campus where one of his core responsibilities was supervising student teachers for teaching practicums. In 2022, he was awarded Hadiah Latihan Persekutuan (HLP) from the Ministry of Education, Malaysia to pursue his doctoral degree, which he is currently undertaking at the Institute of Education (IOE), University College London (UCL), England. He can be reached at [email protected]. Mohammad Shalihin Azim bin Ismail is a student teacher at the Institute of Teacher Education, Ilmu Khas Campus, pursuing his bachelor’s degree in Physical Education. He was once a student athlete at Sabah Malaysian Sports School (SSMS) in 2013-2017. He has undergone numerous classroom observations and teaching practicums over the years as part of the requirement for his degree. Armed with knowledge, enthusiasm, and experience that he has garnered over the course of his undergraduate training, he hopes to become a dedicated teacher in the future to serve the nation. He can be reached at [email protected]. Interested in writing for this blog? Drop us a line!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|